April 24, 2025, | New Delhi, India

In a bold and unprecedented move, India announced the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan on April 23, 2025, following the deadly terror attack in Pahalgam’s Baisaran Valley that killed 26 people, including two foreign nationals and a Navy officer. The decision, part of a five-pronged response by the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, marks a significant escalation in India-Pakistan relations, with far-reaching implications for water security, agriculture, and diplomacy in both nations. This article explores the treaty’s history, the implications of its suspension, its legal standing, and the potential fallout for bilateral ties.

The Indus Waters Treaty: A Historical Overview

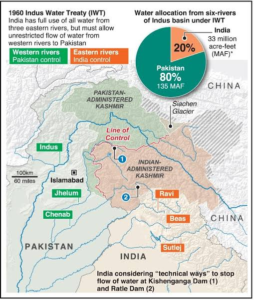

Signed on September 19, 1960, in Karachi by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistani President Ayub Khan, the IWT is a World Bank-brokered agreement governing the sharing of the Indus River system, a lifeline for both countries. The treaty allocates control of the three eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—to India and the three western rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab—to Pakistan. Pakistan receives approximately 80% of the system’s water (99 billion cubic meters annually), primarily for its agriculture-heavy economy, while India controls 20% (33 billion cubic meters), mainly from the eastern rivers.

ALSO READ: Silencing Hate-mongers: Heroism and Humanity in Pahalgam’s Dark Hour

The IWT, hailed as a rare success in India-Pakistan relations, survived three wars, numerous diplomatic crises, and tensions over Kashmir. It includes a three-tier dispute resolution mechanism: the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC), a World Bank-appointed neutral expert, and a Court of Arbitration for unresolved disputes. Despite occasional disagreements, such as those over India’s Baglihar and Kishenganga projects, the treaty has been a global model for water-sharing agreements.

The Pahalgam Trigger and India’s Response

The April 22, 2025, attack by The Resistance Front (TRF), an offshoot of Lashkar-e-Taiba, targeted tourists in Pahalgam, a popular destination in Jammu and Kashmir. Indian authorities linked the attack to Pakistan-based militant groups, citing “cross-border linkages.” In response, the CCS suspended the IWT, closed the Attari-Wagah border, barred Pakistani nationals from SAARC visa exemptions, expelled Pakistani diplomats, and reduced diplomatic staff in both countries. Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri stated the treaty would remain “in abeyance” until Pakistan “credibly and irrevocably abjures its support for cross-border terrorism.”

ALSO READ: How Terrain and Lack of Security Turned Tourists into ‘Sitting Ducks’

The decision echoes earlier rhetoric, notably Prime Minister Modi’s 2016 statement post-Uri attack: “Blood and water cannot flow together.” India had previously notified Pakistan on August 30, 2024, for a treaty review, citing cross-border terrorism, demographic changes, and clean energy needs, but the outright suspension is a dramatic escalation.

Implications for Pakistan

The suspension of the IWT poses severe risks to Pakistan, where the Indus system irrigates 80% of its 16 million hectares of farmland, particularly in Punjab and Sindh, and supports major cities like Karachi and Lahore. Key hydropower plants, such as Tarbela and Mangla, rely on uninterrupted river flows. A halt in water flow data sharing, technical cooperation, or potential Indian storage projects on western rivers could disrupt agriculture, which forms the backbone of Pakistan’s economy, and exacerbate water scarcity amid climate change-induced glacial melt.

Pakistan’s foreign ministry condemned the move, calling the attack a tragedy in “Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir” and denying support for terrorism. The suspension could lead to economic instability, food insecurity, and public unrest, potentially forcing Pakistan to seek international mediation or escalate diplomatic protests.

Implications for India

For India, suspending the IWT signals a hardline stance against Pakistan’s alleged terrorism support, reinforcing domestic political narratives. It frees India from treaty obligations, allowing potential storage or hydropower projects on western rivers, though such moves would take years to implement. However, the decision risks international backlash, as the treaty is a World Bank-mediated agreement, and unilateral suspension could strain India’s relations with global institutions and neighbors like China, which controls upstream Indus sources.

India’s underutilization of its eastern river share has historically allowed excess water to flow to Pakistan. Projects like Shahpurkandi and Ujh, aimed at capturing this water, could now accelerate, boosting irrigation and power generation in Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab. Yet, any significant diversion of western rivers could escalate tensions with Pakistan, potentially inviting military or diplomatic retaliation.

Legal Standing of the Suspension

The legality of India’s suspension is contentious. Under international law, specifically the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), a state may suspend a treaty due to a “fundamental change of circumstances” (rebus sic stantibus) if the change undermines the treaty’s essential basis. India argues that Pakistan’s alleged support for terrorism constitutes such a change, a view articulated by former diplomat Kanwal Sibal and echoed in India’s 2024 notification.

However, the IWT does not explicitly allow unilateral suspension, and its dispute resolution mechanism favors negotiation or arbitration. Pakistan could argue that India’s move violates the treaty’s terms and seek World Bank intervention or appeal to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), though the IWT limits ICJ jurisdiction. The World Bank’s role is procedural, appointing neutral experts or arbitrators, but it could face pressure to mediate. Unilateral suspension risks India’s reputation as a law-abiding global actor, especially since it has upheld the treaty through past conflicts.

Pakistan may also cite humanitarian concerns, as water is a critical resource under international humanitarian law. Any Indian action to drastically reduce water flow could be labeled “water terrorism,” a term used by Pakistani media for India’s past projects.

Bilateral Relations and Regional Stability

The suspension deepens the already fraught India-Pakistan relationship, strained by Kashmir disputes, revoked autonomy in 2019, and ongoing ceasefire violations. The closure of the Attari-Wagah border and visa bans further sever people-to-people and trade ties, while mutual diplomat expulsions signal a near-total diplomatic freeze.

The move has drawn international attention, with the U.S., Russia, and others condemning the Pahalgam attack but urging restraint. Pakistan’s invitation to India for the SCO meeting in October 2025 offers a slim chance for dialogue, but escalating rhetoric—evident in posts on X calling the suspension a “price for terror”—suggests a prolonged standoff.

Climate change adds complexity, as melting Himalayan glaciers threaten the Indus system’s long-term viability. Both nations face water security challenges, and cooperation, not conflict, is critical. The suspension could hinder regional frameworks like SAARC and provoke reactions from China, which has its own water interests in the Indus basin.

India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty is a high-stakes gambit, leveraging water as a strategic tool to pressure Pakistan over terrorism. While it strengthens India’s domestic narrative and opens opportunities for water utilization, it risks legal, diplomatic, and humanitarian fallout. For Pakistan, the suspension threatens economic and social stability, potentially forcing a reevaluation of its security policies. The treaty’s fate now hinges on whether both nations can navigate this crisis through dialogue or slide further into confrontation, with water—a shared lifeline—becoming a new battleground.

As the world watches “‘India suspends Indus Waters Treaty’” trend on X, the question remains: can blood and water ever flow apart without catastrophic consequences?