As Manipur reels from ethnic violence and mass displacement, the state launches a Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls. With thousands missing key documents and sheltering far from home, many fear the exercise mirrors Bihar’s controversial SIR saga—raising concerns of disenfranchisement masked as administrative routine.

By Navin Upadhyay

July 29, 2025: Even as nearly 60,000 people remain displaced due to Manipur’s unrelenting ethnic violence, the Election Commission of India (ECI) is preparing to launch a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls — a move that has drawn widespread criticism for its timing and intent.

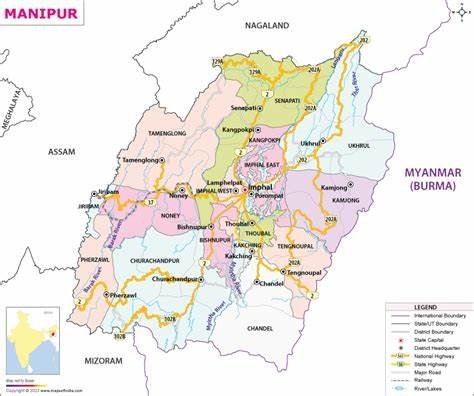

On Monday, the Deputy Commissioner (DC) of Kangpokpi convened a meeting with political parties to discuss the proposed SIR. Though the DC attended virtually, the Additional DC was present on-site. Representatives from the BJP, Congress, and Kuki People’s Alliance (KPA) participated and questioned both the timing of the exercise and the exclusion of Aadhaar as valid identity proof.

“The list of accepted documents didn’t include Aadhaar,” said Dr. Lamtinthang Haokip, who represented the Congress. “That’s bizarre. In a state like Manipur, ravaged by ethnic violence, thousands of people no longer possess any documents. Are you going to disenfranchise tens of thousands living in camps, whose homes have been razed to the ground?” he asked while speaking to The Power Corridors.

READ: Outrage over Excluding Manipur Hills as MPSC Centre

Sources confirmed that BJP representative Thangjaming Kipgen also opposed the exclusion of Aadhaar. “If the Government of India recognizes Aadhaar as a valid identity document, how can the Election Commission ignore it?” he reportedly told the meeting.

“The timing raises eyebrows,” added Dr. Haokip. “It appears to be linked to the narrative the BJP is building in Assam ahead of state elections — trying to polarize voters. Otherwise, what justification could there be for such an exercise in a state still suffering a humanitarian catastrophe?”

While the demand for withdrawal of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar has intensified in the parliament, the Central @BJP4India govt. is pushing for the same in the strife-torn #Manipur without paying attention towards the pains & sufferings of the people.… pic.twitter.com/ydb1KMCnQg

— Dr. Lamtinthang Haokip (@DrLamtinthangHk) July 28, 2025

A Bureaucratic Push Amid Humanitarian Collapse

The SIR, launched by the Office of the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO), is being implemented even as citizens reel from the trauma of displacement. According to official letters dated July 24 and 26, similar meetings were also held in Imphal East and Kangpokpi on July 25 and 28.

But on the ground, the situation is dire. Hundreds of villages have been torched, and thousands of homes looted and burned. Families fled with nothing, often leaving behind essential documents — voter IDs, Aadhaar cards, ration cards, land deeds, school records — all critical for voter registration.

“These aren’t just papers,” said Dr. Thangsing Chinkholal, a well-known physician and social activist in Churachandpur. “They are the proof of identity and existence. Yet the Election Commission seems more interested in paperwork than people. How can anyone think of conducting an electoral revision under these conditions?”

What the SIR Entails — And What It Ignores

The SIR includes:

- House-to-house verification

- Rationalisation of polling stations

- Appointment of Booth Level Agents (BLAs)

- Timelines for draft roll publication

However, it remains unclear how thousands of people, now displaced from their original constituencies, will be accounted for in the revision process. Many have lost all legal documents in the violence — their homes burnt, belongings looted, and papers destroyed. Thousands more have taken shelter outside the state, and may struggle to register online due to the lack of requisite documents they either left behind or that were destroyed in the unrest.

READ: No Arrests, No Names: The Curious Case of Manipur’s Mysterious Arms Recovery

Raher than adopting a rehabilitation-first approach, critics say the ECI appears more concerned with ticking bureaucratic checkboxes — even as people remain in limbo, without homes or official identities.

Ethnic Control or Electoral Inclusion?

Many see this voter revision not as an inclusive democratic exercise, but as a veiled attempt to further the political agenda of former Chief Minister N. Biren Singh and Imphal’s armed militia

Arambai Tenggol, who have long called for identifying so-called “illegal immigrants.”

Ironically, Singh himself, in a memo to the Governor earlier this year, estimated the number of such immigrants at just 6,000 — a figure dwarfed by the tens of thousands displaced and at risk of being disenfranchised.

“This is not electoral justice,” said Dr. Thangsing Chinkholal. “It’s an administrative tool being used for ethnic control. How can anyone propose this in a state facing a tragic humanitarian crisis? This is nothing but a political agenda to target minorities.”

By moving ahead with the revision while thousands remain homeless and undocumented, the Election Commission risks turning a cornerstone of democracy into an instrument of exclusion and division.

“If the goal is to clean up the voter list,” said Dr. Chinkholal, “then clean up the mess left by the violence first. Our people have lost everything — don’t take our vote too.”