Revenue Minister Keshab Mahanta told the Assembly that multiple organisations got land, but BJP’s dominant share raised concerns over neutrality and transparency.

BY PC BUREAU

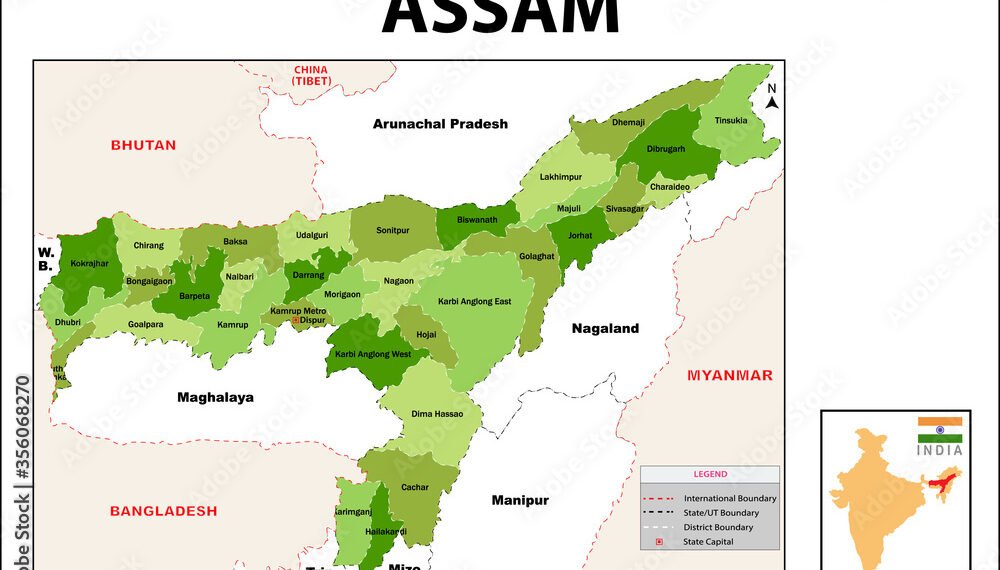

November 29, 2025: The Assam Assembly on Friday witnessed renewed scrutiny of the state’s land distribution practices, after the government disclosed that the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been allotted government land in 35 locations across multiple districts since 2016. The revelation came during Question Hour, in response to a query by Independent MLA Akhil Gogoi, who has frequently raised concerns over resource allocation and political transparency.

Revenue and Disaster Management Minister Keshab Mahanta confirmed the allotments and offered a district-wise breakup, noting that the plots were sanctioned over the past nine years primarily for the construction of party offices. The information has amplified an ongoing debate on whether state resources are being equitably distributed—or whether political parties in power enjoy institutional advantages.

Distribution Across Districts

According to the minister, the BJP’s 35 plots are spread across key districts, with Dibrugarh and Nalbari topping the list—each receiving five allotments. Districts such as Dhubri, Kamrup (Metro), and Sonitpur saw three allotments each, indicating a concentration of party infrastructure expansion in both Upper Assam and central districts.

These allotments, Mahanta clarified, are not exclusive to the ruling party. Between May 10, 2016, and the present, 13 other organisations, including political parties and civil-society bodies, have also been granted government land. The list includes the BJP’s coalition partner Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), the Congress, and associations such as the Dibrugarh District Journalist Association.

Dhubri Emerges as a Key Hotspot

While Dibrugarh and Nalbari saw the largest number of BJP allotments, Dhubri district received the highest number of total government land allocations among the non-BJP organisations during the same period. The district’s seven allotments indicate a broader reconfiguration of administrative and political presence in western Assam.

Government’s Defence: ‘Not Just BJP’

Minister Mahanta emphasised that the allotments were part of a larger, structured process under existing land policies, and not targeted benefits to any single political group.

“Between 2016 and now, 13 other organisations, including political parties, have been allotted government land in various districts,” he said, noting that land was sanctioned based on available plots and procedural approvals.

The government’s clarification is aimed at countering criticism that the ruling party is using state land for political consolidation. However, the disclosures also highlight the BJP’s push to expand its organisational footprint across rural and semi-urban centres—an infrastructural strategy that mirrors its aggressive electoral outreach in recent years.

Why the Issue Matters

Land distribution is a politically sensitive subject in Assam, a state where land scarcity, migration pressures, and ethnic claims frequently overlap.

Against this backdrop, any large-scale allocation—especially to political entities—inevitably attracts scrutiny.

Opposition leaders argue that even if the process was legal, the optics of the ruling party receiving the lion’s share of land allotments raise questions about neutrality.

Independent voices like Akhil Gogoi have demanded greater transparency, seeking details on:

The criteria used to select recipient organisations

Whether other parties or community groups applied but were rejected

How the allocations align with the state’s stated land-use priorities

READ: IndiGo, AI Brace for Delay, Cancellation as A320 Fixes Begin

Political Significance

The BJP’s land allotments come at a time when the party is consolidating physical infrastructure across Assam, including new district offices and organisational hubs. Establishing permanent buildings in strategic districts helps strengthen the party’s grassroots network and long-term presence—benefits that extend far beyond electoral cycles.

Simultaneously, the fact that other political parties and civil groups also received land gives the government a buffer against accusations of partisanship. Yet the disproportionate number of plots allotted to the ruling party underscores the structural advantage often enjoyed by those in power.

The Larger Pattern

Since 2016—when the BJP first formed the government in Assam—the party has dramatically expanded its organisational capacity. The land allotments appear to be part of that broader strategy, correlating with the party’s internal reorganisation, increased membership drives, and deeper penetration into districts where its influence was traditionally weaker.

Districts like Dibrugarh, Nalbari, and Kamrup Metro—which feature prominently in the allotment data—are also key political battlegrounds or administrative hubs, making them logical choices for new party offices.

What Happens Next

With the information now part of the Assembly record, the issue is likely to spark further debate—both in the House and outside. Opposition parties may demand a detailed audit of land allocation practices, amid calls for a more transparent and uniform framework.

Civil society groups, particularly in districts where land scarcity is acute, may also push back against political land allotments, arguing that public resources should prioritise schools, health infrastructure, or community institutions.

For the BJP, however, the disclosures reaffirm the party’s organisational expansion—and may even be framed as routine administrative decisions necessary for modernising political infrastructure across the state.