Sonam Wangchuk, Ladakh’s solar innovator and environmental crusader, sits behind bars in Jodhpur under the National Security Act for demanding constitutional safeguards. Thousands of miles away, NSCN leader Thuingaleng Muivah continues to speak freely of Naga sovereignty. The contrast lays bare India’s selective outrage — when peace is punished but secession finds space, questions arise over what truly threatens the nation.

BY Navin Upadhyay

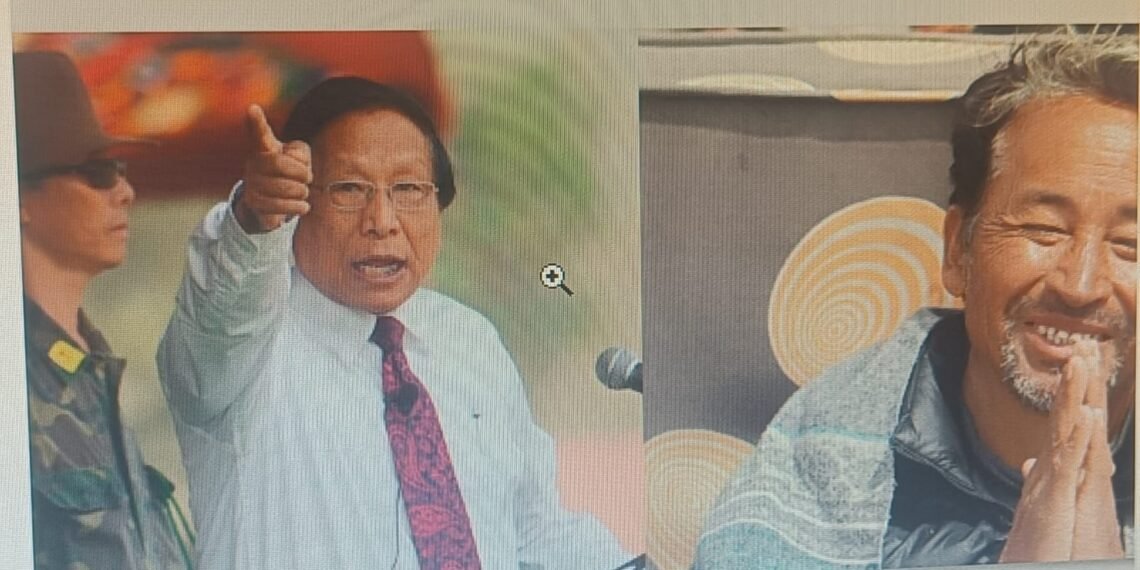

Two men, two frontiers, two Indias. In the frozen desert of Ladakh, Sonam Wangchuk — the engineer-monk who warmed soldiers’ tents and inspired a generation with his solar science — now languishes in Jodhpur Central Jail under the National Security Act. Over a thousand kilometres east, in Nagaland and Manipur’s hills, Thuingaleng Muivah — the ageing insurgent leader who still preaches the dream of an independent “Nagalim” — moves freely, addressing gatherings that question India’s borders. The contrast has stirred a national reckoning: why does peaceful protest in Ladakh invite imprisonment, while open defiance in the Northeast meets silence?

Wangchuk’s detention under the National Security Act (NSA)—a law reserved for threats to India’s sovereignty and public order–came after a series of peaceful demonstrations demanding constitutional safeguards for Ladakh under the Sixth Schedule, protection of its fragile ecology, and a more transparent governance structure. These were movements rooted in Gandhian restraint — processions of students and monks, slogans about the Himalayas, and appeals for autonomy. Yet the administration invoked a law reserved for threats to the nation’s security — the NSA — to justify his arrest.

Under the Act, authorities can detain individuals for up to a year without formal charges if they believe their actions are “prejudicial to the security of India or public order.” In Wangchuk’s case, local police cited his “potential to incite unrest.” Legal experts, however, have called the move “grossly disproportionate.” Even retired Army officers, who once commanded units in Ladakh, have come out in his defence.

“Sonam’s patriotism is beyond question,” said a retired lieutenant general who served with the XIV Corps in Leh. “He has done more for the country’s border people than most bureaucrats ever will.” Others have described his detention as “a betrayal of the very ideals he embodies.”

Indeed, Wangchuk’s story is one of deep alignment with India’s frontiers — building solar schools for children, campaigning for sustainable development, and defending the fragile Himalayas from reckless industrialisation. That such a figure should be detained under a law designed for terrorists or spies has confounded many.

Muivah Vouches for secession, Naga Flag, sovereignty

Meanwhile, nearly two thousand kilometres away in Manipur’s hills, another figure — Thuingaleng Muivah, the ageing general secretary of the National Socialist Council of Nagalim (Isak-Muivah) — travels freely across Naga territory. At 91, Muivah remains the face of the decades-old Naga struggle, and his recent homecoming to Senapati and Ukhrul after five decades was marked with celebrations, public parades, and speeches that left little doubt about his continuing ideological stance.

At a gathering in Senapati in September, Muivah told a crowd of thousands, “The Naga national flag and the Naga constitution are non-negotiable. We are not part of India or Burma — we have our own history and our own destiny.” His words, met with cheers, were reported widely in Naga newspapers.

🚨Look at these armed men & women in uniform?

Not Indian forces—they’re NSCN-IM commandos.When Muivah visited Manipur, he came flanked by his militia, insulted India’s Constitution &called parts of Manipur “Southern Nagaland.”

A direct challenge to India’s unity & sovereignty. pic.twitter.com/qlKP43Jfc8

— Abiema Lisham (@AbiemaLisham) October 31, 2025

In another address at Ukhrul, his home district, Muivah said, “We have not surrendered the sovereignty of Nagalim, and we never will — whether it is today or tomorrow.” For Delhi, these statements would appear to strike at the very idea of national unity. Yet no charges have followed — no preventive detention, no summons, no official rebuke.

This paradox — Wangchuk behind bars for advocating constitutional protection within India, and Muivah speaking freely about separation — captures something larger about how the state defines “anti-national activity.” In one case, dissent against administrative apathy is criminalised. In the other, a long-running secessionist narrative is tolerated as part of a political dialogue.

Officials familiar with security policy argue that the difference lies in “strategic context.” Muivah, they say, operates under the 2015 Framework Agreement, signed between the NSCN-IM and the Government of India, which keeps the Naga talks within a ceasefire mechanism. Arresting him now would risk derailing decades of negotiations. But this pragmatism sits uneasily with those who see the law applied without consistency.

Across the Naga hills, Muivah’s words are not abstract. At Senapati, his speeches invoked the “integration of all Naga areas” — a phrase that includes territories in Manipur, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and even Myanmar. “Our flag is our life,” he said, echoing earlier declarations that “the Naga constitution, the Yehzabo, is non-negotiable.”

These are not isolated remarks. Over recent months, the Morung Express and Nagaland Post have published excerpts from NSCN-IM meetings where Muivah reaffirmed “the sovereign rights of Nagalim” and criticised Delhi for “betraying the spirit of the Framework Agreement.” His call for a separate flag and constitution remains the movement’s core demand.

READ: NDA Sankalp Patra: Promising the Moon — and More — for Bihar

READ: Epstein Link: Prince Andrew Cast Out: No Titles, No Palace, No Return

Contrast this with voices from Ladakh, where Wangchuk’s arrest has stunned even those usually aligned with the administration. “We never imagined he would be treated like a criminal,” said Tsering Dorjay, a local activist in Leh. “His only demand was constitutional safeguards — the same that other hill states already have.”

For Ladakh, the disillusionment runs deep. When Article 370 was revoked in 2019, many Ladakhis celebrated their new Union Territory status. But six years later, they say promises of self-governance remain unmet. Wangchuk’s movement was seen as a moral nudge, not a rebellion.

“The government could have engaged him,” said a senior journalist from Leh. “Instead, they’ve made him a symbol of how even the most loyal voices can be silenced.”

Veterans Speak Out

Maj Gen G.D. Bakshi (Retd.): “China’s threat looms over Ladakh. Sonam Wangchuk is not an agitator but a national asset. The government must address Ladakh’s issues before they spiral further.” — HimbuMail, 3 Oct 2025

Maj (Retd.) Panang Tashi, Ladakh Veterans’ Forum: “Wangchuk equipped our soldiers against the cold that kills faster than bullets. His arrest is a gift to our adversaries. Jail a patriot, and you jail Ladakh’s spirit.” — Leh protest, 1 Oct 2025

SM Tsering Namgyal, ex-Army and national ski champion: “His solar tents saved lives on the frontlines. Arresting him for demanding constitutional rights is a betrayal of those he served.” — Video on X, 19 Sept 2025

A Ladakh veterans’ montage summed it up: “He armed us against the cold, not the enemy. Negotiate, don’t incarcerate.” — SECMOL advocacy video

Veterans warn that Ladakh is not Assam and Wangchuk is no agitator. This Buddhist-majority border region supplies India’s sentinels. Yet a 15-day hunger strike for Sixth Schedule safeguards drew an NSA charge meant for terrorists, and the activist was flown 1,200 km to a desert prison.

Charges of NSA Misuse

The NSA, under which he is detained, has a long history of controversial use. In Uttar Pradesh and Assam, it has been invoked against protestors accused of cow slaughter or anti-CAA demonstrations. In Jammu & Kashmir, hundreds were detained under its provisions after the abrogation of Article 370. The law’s vagueness — “activities prejudicial to national security” — makes it a flexible instrument for political control.

Legal scholars note that the NSA’s preventive powers were designed for exceptional circumstances — terrorism, espionage, or large-scale public disorder. But over the years, it has been used for everything from social media posts to local agitations. “It’s become the state’s tool of choice when it can’t justify a charge in court,” said senior advocate Indira Jaising in a recent seminar.

The contrast with the government’s hands-off approach toward Muivah, however, raises difficult questions. “If India can negotiate with those who took up arms, why not dialogue with those who use words?” asked a former intelligence officer who served in Nagaland during the ceasefire years.

Part of the answer lies in optics. The Naga movement, with its ceasefire agreements and international dimensions, is seen as a legacy issue — a slow-moving negotiation to be managed, not provoked. Ladakh’s protests, by contrast, strike at the heart of Delhi’s current policy narrative: strong governance, stability, and control in border regions.

Yet the symbolism is impossible to miss. Wangchuk, the reformer who taught Himalayan children to build ice stupas, is painted as a potential disruptor. Muivah, who once led an insurgency against India, is treated as a partner in dialogue. The irony is bitter — and deeply revealing.

Even within the security establishment, there is discomfort. “You cannot build loyalty by punishing love for the nation,” said a retired brigadier who served in the Northern Command. “Wangchuk is the kind of man who inspires people to serve in the army. To treat him as a threat is absurd.”

Political observers suggest that the episode reflects a shift in how dissent is perceived in India’s peripheries. “In the Northeast, where the state has long relied on negotiation and ceasefire, a certain tolerance exists for anti-establishment rhetoric,” said a Guwahati-based political scientist. “In Ladakh, however, there’s no insurgent past — so dissent is seen as deviation.”

Meanwhile, Wangchuk’s supporters continue to hold candle marches in Leh, demanding his release. His wife and colleagues maintain that he has been denied adequate access to legal counsel. “He’s been moved so far from home that even his voice is silenced by geography,” one friend said.

To his followers, Muivah remains the patriarch of a cause larger than politics. To others, he is a reminder of unfinished history. But to the broader Indian public, his freedom and Wangchuk’s incarceration represent two sides of a paradox — a country that negotiates with separatists even as it detains its reformers.

As the Himalayan winter deepens, Leh’s skies shimmer with prayer flags — symbols of peace, not protest. And somewhere behind the stone walls of Jodhpur prison, Sonam Wangchuk remains India’s most paradoxical prisoner: a patriot punished for believing his nation could do better.