Editor’s Note: As part of our ongoing commitment to serve as an advocacy platform for peace in Manipur, we continue to welcome “opinion” pieces from all communities. We urge contributors to refrain from language that could be interpreted as inciting violence or hatred. In line with this initiative, we present a write-up by HS Benjamin Mate, Chairman of the Kuki Organisation for Human Rights Trust (KOHUR). Please mail your write-up at: novinkn@gmail.com

BY H. S Benjamin Mate

The standard narrative of Manipur’s merger with the Indian Union in 1949 emphasises coercion, loss of sovereignty and the heroic resistance of the Meitei revolutionary Hijam Irabot Singh. Such a reading implies a unified populace opposed to integration. Yet Meitei society in the late 1940s was deeply stratified and politically divided. This article revisits the historiography of the merger to show that anti‑monarchial sentiment and class grievances played as large a role as nationalism. It argues that for many valley Meiteis, abolition of the feudal monarchy and its oppressive practices was the overriding goal, and that integration with democratic India was welcomed as a means to end aristocratic privilege. Drawing on contemporary accounts, it demonstrates that the Manipur State Congress Party (MSCP) explicitly campaigned for merger and that common people, while politically inexperienced, did not mount any mass protest. The article contends that modern portrayals of universal opposition obscure this complex reality and have been amplified to serve current political demands.

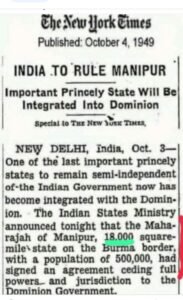

On 21 September 1949 Maharaja Bodhchandra Singh signed the Merger Agreement with the Government of India in Shillong. In contemporary Manipuri politics this date is commemorated as “Black Day,” symbolising the loss of an independent kingdom. Central to this memory is Hijam Irabot Singh, revered as a revolutionary who opposed the merger. However, this prevailing narrative often overlooks the internal dynamics of Meitei society. This article interrogates the binary of “coercion versus resistance” by examining the socio‑economic conditions that fostered anti‑monarchial feeling and the political divisions within the Meitei community.

- The Feudal Context: Monarchy and Social Oppression

Pre‑merger Manipur was a constitutional monarchy in form but a feudal society in practice. The Maharaja and his court maintained authority through institutions like the Lallup (corvée labour) and by controlling trade in rice and forest products. The Second Nupi Lan (Women’s War) of 1939—sparked by the export of rice during famine conditions—revealed widespread anger among Meitei women toward both colonial officials and the Maharaja’s durbar. Popular discontent was compounded by economic monopolies granted to Marwari traders and enforced by the state. Such practices entrenched a perception that the monarchy and its Brahmin advisers protected aristocratic interests while ignoring the hardships of ordinary Meiteis.

The promulgation of the Manipur State Constitution Act 1947 introduced an elected Legislative Assembly, raising hopes that democratic governance would replace autocracy. Yet the council of ministers remained subordinate to the palace, and the appointment of a dewan (prime minister) by the governor of Assam in 1949 further undermined Meitei autonomy .These developments intensified calls for systemic change.

- Hijam Irabot Singh and the Anti‑Feudal Struggle

Hijam Irabot Singh (1896–1951) has become a symbol of resistance to the merger. His legacy, however, centres on anti‑feudal revolution rather than anti‑unionism. As vice‑president of the Nikhil Manipuri Mahasabha (later reorganised as a secular political body), he advocated democratic representation and land reform. When the Maharaja rejected proposals for a responsible government, Irabot and his colleagues resigned from official posts and mobilised peasants and women. After the Pungdongbam incident in 1948 he went underground and organised an armed communist movement, dying in 1951. Irabot opposed the merger because he believed it preserved the Maharaja’s status rather than dismantling feudalism; his goal was a socialist republic of Manipur.

READ: 42 Years On and Eyeing Polls, Himanta Revives Forgotten Nellie Massacre Report

III. Pro‑Merger Lobby and Evidence of Popular Support

- The Manipur State Congress Party (MSCP)

Contrary to the perception of universal resistance, a pro‑merger lobby existed within the Meitei political class. The Manipur State Congress Party, an affiliate of the Indian National Congress, represented what Lal Dena calls “lumpen pro‑Indian nationalists” . On 15 August 1947, during India’s independence celebrations at the Polo Ground in Imphal, MSCP leaders publicly declared their intention to launch a movement to merge Manipur with India . The party argued that integration with the Indian Union would bring modern education, infrastructure and economic development, and provide an opportunity to break the back of the feudal order. By April 1949 the MSCP had resolved to send a delegation to the All India Congress Committee in Delhi to press for immediate merger.

2. Political Indifference and Absence of Mass Protest

Elections held in June–July 1948 produced a coalition ministry dominated by regional parties. The assembly remained divided between pro‑merger Congressmen and pro‑autonomy nationalists. When reports of the draft merger agreement reached Imphal, the assembly met on 29 September 1949 and declared the agreement null and void; however, this protest came too late and lacked widespread mobilisation . Professor Senjam Mangi Singh notes that at the time of the merger “Manipur had a very low level of political culture. Except for a small politically aware section of the population, the common people remained politically ignorant” . In other words, there was no large‑scale uprising against the merger. Oral testimonies collected by scholars describe villages where the end of royal authority was greeted with Thabal Chongba dances and fireworks—a sign that many commoners saw the dissolution of monarchy as liberation rather than loss of nationhood. While quantitative data are scarce, the absence of sustained resistance and the visible rejoicing suggest that significant sections of Meitei society accepted, if not actively supported, integration with India.

- Reasons for Pro‑Merger Sentiment Among Meiteis

Several factors explain why many Meiteis viewed the merger favourably:

- Anti‑Monarchial Grievances: Decades of forced labour, economic exploitation, and social exclusion under the monarchy created a desire for change. The merger promised to abolish these practices and replace feudal privileges with republican citizenship.

- Democratic Aspirations: The MSCP and other modernist elites believed that joining the Indian Union would ensure a democratic constitution and full adult franchise—rights that the Maharaja had been reluctant to extend. The promise of constitutional safeguards for hill tribes and minority groups under Article 371C also appealed to inclusive nation‑building.

- Socio‑Economic Benefits: Integration offered access to national schemes, educational institutions and markets. Many valley Meiteis sought improvement in infrastructure, employment opportunities and social mobility which they associated with being part of a larger nation.

- Reappraising Anti‑Merger Narratives and Contemporary Politics

Although the merger did not involve a popular plebiscite and was signed under questionable circumstances, evidence suggests that opposition was far from unanimous. While Hijam Irabot and other nationalist leaders protested the agreement, the absence of widespread agitation and the proactive campaign of the MSCP point to a divided political landscape . Contemporary commemorations of “Black Day” have at times projected an image of total resistance to legitimise demands for constitutional changes such as Scheduled Tribe status for Meiteis or special economic packages. Such commemorations serve as strategic tools in negotiations with the central government. A more balanced historiography must acknowledge both the anti‑feudal revolution spearheaded by Irabot and the pro‑merger aspirations of many ordinary Meiteis.

The merger of Manipur with the Indian Union was a product of interlocking forces: external diplomacy, internal class struggle and rival nationalist visions. For large sections of the Meitei population, weary of feudal domination, the agreement represented the culmination of a long struggle against the Maharaja’s oppressive regime. The Manipur State Congress Party championed integration and mobilised supporters, while the common people displayed indifference or relief rather than revolt . Irabot’s anti‑monarchial revolution, though anti‑integrationist, coexisted with genuine pro‑merger sentiment rooted in the desire for social justice. A nuanced understanding of this history challenges monolithic narratives and invites a more inclusive conversation about Manipur’s past and its implications for contemporary identity politics.

(The Author is Chairman of the Kuki Organisation for Human Right Trust)