Editor’s Note: As part of our ongoing commitment to serve as an advocacy platform for peace in Manipur, we continue to welcome “opinion” pieces from all communities. We urge contributors to refrain from language that could be interpreted as inciting violence or hatred. In line with this initiative, we present a write-up by Seilen Haokip, spokesperson of the Kuki National Organisation (KNO). Please mail your write-up at: novinkn@gmail.com

BY Sailen Haokip

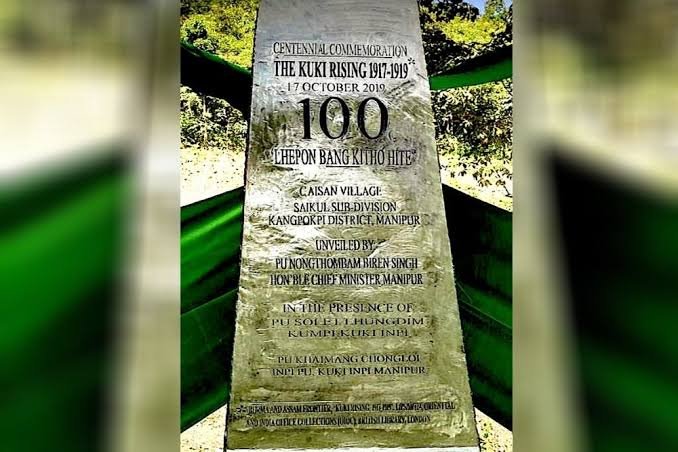

There is a great deal of confusion surrounding the Anglo-Kuki War of 1917–1919. Much of this has been deliberately created to marginalize the role of the Kukis in India’s struggle against British colonial rule. These narratives are often propagated by elements who have never shed a drop of blood for India, yet have stoked insurgency and sought secession. Such attempts reflect a troubling disregard for historical accuracy. They aim to erase a defining anti-colonial struggle that spanned over two years and encompassed vast territories across present-day Manipur, the Somra Tract, and the Chin Hills.

Casting aspersions on Kuki historians and reducing the resistance to isolated incidents ignores a wealth of contemporaneous records that clearly establish the scale, organization, and significance of the conflict.

Young Kuki Slams Distortion of Anglo-Kuki War History https://t.co/hXYfGDpR8u #AngloKukiWar#KukiHistoryMatters #YoungKukiVoice#DecoloniseHistory #ManipurNarratives#TruthAndMemory

— POWER CORRIDORS (@power_corridors) October 21, 2025

A review of historical and contemporaneous records of the 1917–1919 Kuki War against the British reveals the following:

- “The operation was carried out by the combined forces of Assam and Burma military police: 6,234 combatants, 696 non-combatants, and 7,650 transport carriers took part in the fight.” (Brig. Gen. CEK Macquoid)

- “…the most formidable with which Assam has been faced for at least a generation.” (Proceedings of the Chief Commissioner of Assam, 1919)

- “Casualties: British troops – 60 dead, 142 wounded, 97 dead due to diseases; Kukis – 120 killed; 126 Kuki villages burnt down, 140 villages surrendered.” (WL Shakespeare, 1929)

- “The largest series of military operations conducted on this side of India.” (WL Shakespeare)

- “A sum of Rs 1,67,441/- as war reparation was recovered from the Kukis, in cash and in the form of penal labour.” (NAI, Foreign & Political Dept., 1919)

- “The Kuki Rising of 1917–1919 is the most formidable with which Assam has been faced for at least a generation. Rebel villages were held over some 6,000 square miles of rugged hills surrounding the Manipur valley and extending to the Somra Tract and the Thaungdut State in Burma.” (Extract from the proceedings of the Chief Commissioner of Assam, 27 Sept 1920)

Need more be said?

Sifting through this epic historical event, some modern narratives attempt to conflate Manipur’s history unevenly. They focus on citing Kuki ethnic Mizo and Chin, privileging the role of Chingakha Sanajaoba — whose activity ceased after a brief initial incident — and reducing Naga participation to a few individuals reneging on prior agreements. In the same breath, such accounts attempt to subsume the Kuki narrative into a vague collective of “Naga, Meitei, and Thadou alike under shared skies.” This approach defies logic and falls short of professional journalistic ethics.

Comparing the Kuki Rising (1917–1919, Anglo-Kuki War) with the Khomjom battle (Anglo-Manipur War, 31 March–27 April 1891) is a grave travesty of history.

Contrary to some misreadings, the Kukis were not a part of the Kangleipak kingdom ruled by Meitei kings. Historically, Kuki chieftains and Meitei rulers shared mutual respect for each other’s identity, territory, and polity — a relationship that fostered peaceful coexistence.

READ: Trump Admin. Clarifies $100,000 H-1B Fee, Relief for Indian Students

READ: After Hawking Nagalim Dreams for 50 Years, Muivah Returns Home — Empty-Handed

During British colonial rule, the separation of administration between the hills and the valley continued: a political agent oversaw the hill people, while the British administered Kangleipak through the Meitei king. At no point did either community exercise governance over the other. Following historical precedent, this status quo carried into present-day Manipur (a colonial construct), with constitutional safeguards for the hills under Article 371C and provisions for the Hill Area Committee. Unfortunately, these provisions were weakened over decades by self-serving majoritarian politics. The valley, representing 53% of the population, was allocated 40 seats against 20 seats for the 47% hill population in the 60-seat Legislative Assembly — a lopsided arrangement that entrenched inequity over 50-plus years.

This inequity extended beyond legislative representation. Positive discrimination provisions for Other Backward Classes (OBC) and Scheduled Castes (SC) were leveraged to press for Scheduled Tribe (ST) status, culminating in attempts by the chief minister to expand ancestral Kangleipak territory into the hills and illegally evict Kuki forest dwellers under the guise of state authority.

Amidst prolonged trials and tribulations, the once-cherished memories of Kuki history were buried. Yet, a new dawn broke on 3 May 2023, when adversity became an opportunity to reclaim and preserve Kuki heritage.

Truth must be told — not rewritten or diminished by flawed, self-serving interpretations.