Nearly five years after overturning the 2020 election, the Myanmar junta is pushing ahead with election despite civil war, mass displacement and the exclusion of opposition parties.

BY PC Bureau

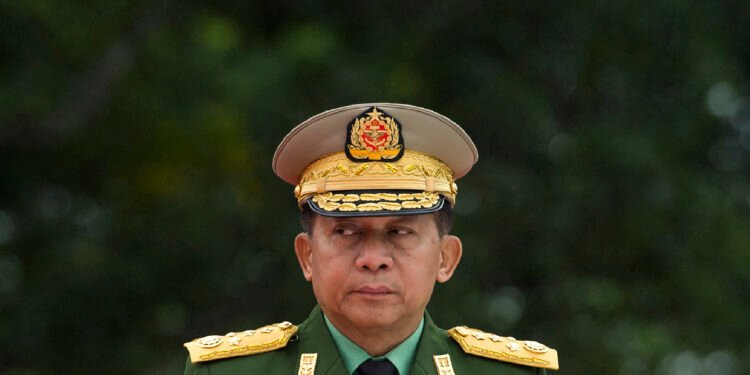

December 23, 2025: With Myanmar’s military junta set to begin voting from December 28, coup leader Min Aung Hlaing has intensified efforts to portray the heavily restricted polls as a step toward democracy, even as large sections of the population appear determined to reject them.

Addressing military officers and their families in Magwe on Saturday, Min Aung Hlaing warned that refusing to vote amounted to rejecting “progress toward democracy.” The message was delivered to one of the few audiences still compelled to listen, underscoring the junta’s struggle to generate public enthusiasm for an election widely dismissed as a façade to legitimise military rule.

Nearly five years after the army annulled the results of the 2020 general election and overthrew the elected civilian government, the junta is pressing ahead with a three-phase vote—on December 28, January 11, and later in January—despite ongoing civil war and widespread political repression. The 2020 polls, verified by domestic and international observers, had seen the National League for Democracy (NLD) secure a landslide victory, with ballots cast by around 27 million voters later declared void by the military.

To fill the visible vacuum of public support, junta-aligned celebrities have been dispatched to recently recaptured towns in northern Shan State, including Kyaukme and Nawnghkio, to stage performances and urge residents to vote. Senior military leaders, including Min Aung Hlaing and his deputy Soe Win, have also toured Yangon, Mandalay, Magwe and Kachin State, appealing for support for candidates with “defence-minded views” who can “work in harmony with the military.”

Myanmar’s election laws do not mandate a minimum voter turnout, but the junta is keen to project participation to the international community. The stakes are high for a regime that has lost control over large swathes of the country to pro-democracy forces and ethnic armed groups.

This is what a junta run election looks like, a hollow performance, stripped of legitimacy!

It can never be able to represent the nationwide and the truth is clear, no one is genuinely invested in casting a vote for such a farce.#WhatsHappeningInMyanmar #Myanmar pic.twitter.com/E6jCASqUd9

— Robert Minn Khant (@minn_robert) December 20, 2025

Fifty-seven parties are contesting the polls, with the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) fielding by far the largest number of candidates. Under the junta-drafted Constitution, 25 percent of parliamentary seats are reserved for military appointees, meaning the USDP needs just over a quarter of the vote to secure effective control. Critics say the system is designed to guarantee continued military dominance, a claim reinforced by reports that some parties have been disbanded to limit competition.

Min Aung Hlaing has repeated his pledge to hand power to the winning party, but scepticism remains widespread. Observers believe he could reinstall himself as president with the backing of military lawmakers and the USDP.

International reaction has been largely hostile. Western democracies and organisations including the United Nations have rejected the election as neither free nor fair, describing it as a rebranding of martial law. The junta, however, insists the process has international recognition, citing support from countries such as China, India, Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Cambodia and Thailand.

READ: Rahul Targets BJP Over ‘Election Integrity’ in Berlin Address

READ: Protests Erupt Outside Bangladesh High Commission in Delhi Over Hindu Man’s Lynching

Voting will not take place in rebel-held areas, and the junta has conceded that elections cannot be conducted in around one in seven constituencies. In territories under its control, polling is due to begin at 6 am on Sunday, including in Yangon, Mandalay and Naypyitaw.

Public apathy and fear dominate the run-up. “The military are just trying to legalise the power they took by force,” a resident of Myitkyina told AFP, vowing to boycott the poll. Others said they were worried about repercussions if they abstained, as the junta prosecutes dissent under sweeping laws criminalising criticism or “disruption” of the election. More than 200 people have already been charged under these provisions.

Former civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi remains jailed, serving a 27-year sentence on charges widely dismissed by rights groups as politically motivated. Her son, Kim Aris, said he did not believe she would consider the elections meaningful. The NLD has been dissolved, along with most parties that contested the 2020 polls, leaving a ballot dominated by military allies. New electronic voting machines will not allow write-in candidates or spoiled ballots, further narrowing voter choice.

Around 22,000 political prisoners remain in detention, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, while conflict continues to escalate. The junta has intensified military operations ahead of the vote, reclaiming some territory while launching air strikes on areas beyond its control. An air strike on a hospital in Rakhine State earlier this month killed more than 30 people, according to local aid workers—an allegation the military denies.

Since the coup, Myanmar has been plunged into a nationwide conflict involving pro-democracy guerrilla forces and long-standing ethnic armed groups. There is no official death toll, but estimates by conflict monitors suggest around 90,000 people have been killed. More than 3.6 million have been displaced, and the UN says nearly half the population is living in poverty.

While a handful of political figures argue the election offers a possible path forward, many inside and outside Myanmar remain unconvinced. “There are many ways to make peace, but they have chosen an election instead,” said a fighter from the pro-democracy People’s Defence Force, vowing to continue the struggle.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres has summed up international sentiment bluntly: “I don’t think anybody believes those elections will contribute to solving the problems of Myanmar.”

As the first ballots are cast, the junta faces a reality starkly at odds with its rhetoric—an election unfolding amid war, repression and a population that, for the most part, appears unwilling to confer legitimacy on military rule.