Editor’s Note: In observance of the second anniversary of the tragic events that engulfed Manipur on May 3, 2023, The Power Corridors is inviting opinion makers and individuals from all sides of this ongoing crisis to share their suggestions for restoring peace and prosperity to the region. As part of this initiative, we feature a detailed article by Dr. Seilen Haopkip, the spokesperson of the Kuki National Organisation (KNO). While thanking Dr Seilen for his contribution, I take the opportunity to encourage other prominent voices within both the Meitei and tribal communities to come forward and express their perspectives. You may send your write-up at novinkn@gmail.com. We intend to compile these contributions and forward the collection to the Ministry of Home Affairs for their consideration of the voices from Ground Zero. Thank you. Navin Upadhyay

Time to Revisit the Forgotten Past: Separate Administrations for Kuki Zo and Meitei:

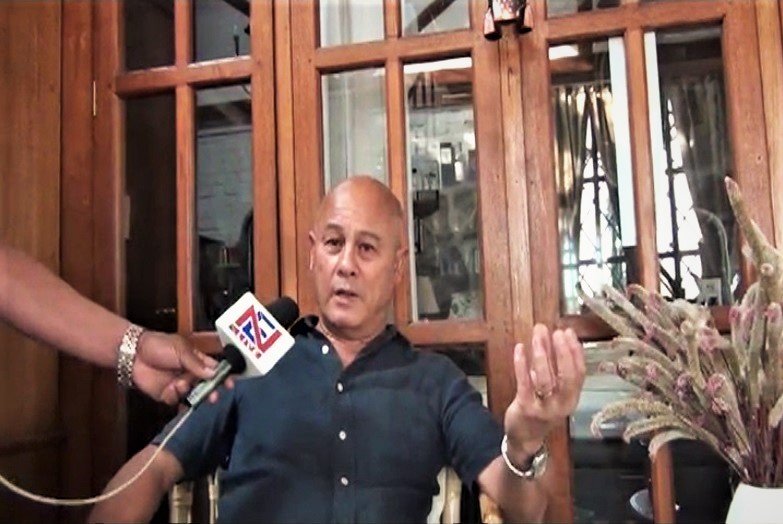

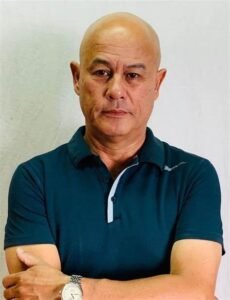

BY Dr. Seilen Haokip

BY Dr. Seilen Haokip

3 May 2025 is the second anniversary of the devastating violence of 3 May 2023; the state remains deeply fractured—ethnically, politically, and emotionally. A growing chorus of historians, tribal leaders and constitutional scholars argues that the solution may lie not in forced integration, but in restoring the time-honoured practice of separate governance for the valley-dwelling Meitei and the hill-dwelling Kuki Zo.

The conflict between the majority Meitei and minority Kuki-Zo communities has reached a point of no return under the current unitary administrative framework. The time has come to face a sobering truth: peace will not come from forced coexistence but from constitutionally guaranteed autonomy rooted in historical precedent.

A Legacy of Separate Rule

Separate administration is not new. Long before the British arrived in 1824, the Meitei kingdom (confined to the fertile Kangleipak valley) and the myriad Kuki-Zo chieftainships in the surrounding hills coexisted under distinct administrations. Even under colonial rule, the British maintained this divide for ‘administrative convenience’, drawing the modern boundaries of Kangleipak, which for their political and administrative convenience was constructed as ‘Manipur’, including the surrounding hills where the Meitei monarch’s administration never was. The boundaries were drawn in stages—West (1832), East (1834), North (1873), South-East (1894) and South (1900)—yet never unifying the valley and hills under a single local authority.

Post-Independence Imbalance

When Manipur acceded to India in 1949, the nascent government chose to preserve those colonial boundaries. Article 371C of the Constitution established a Hill Areas Committee to protect tribal interests—on paper. However, in a 60-seat assembly, 40 seats were assigned to the Meitei majority (around 44 percent of the population, including some non-Meitei) and only 20 to tribal communities (41 percent). Advocates say this ‘lopsided representation’ rendered Article 371C toothless and denied Manipur’s hill tribes the Sixth Schedule safeguards enjoyed by other Northeast states.

ALSO READ: KIIT Under Scrutiny After Second Suicide of a Nepali Student

‘Our hill communities have been second-class citizens in their own land’, says Dr L Thangjam, a legal scholar at Imphal University. “The colonial legacy was never dismantled; it was merely repackaged to favour the valley majority.”’

Echoes of Discontent

Decades of underrepresentation have fuelled two parallel insurgencies. The NSCN-IM, predominantly Tangkhul Naga, continues to press for incorporation of Naga-inhabited areas into a ‘Greater Nagalim’. Meanwhile, Kuki-Zo groups entered a Tripartite Suspension of Operations with the Centre and the Manipur government, seeking political and territorial autonomy within the state of Manipur, India.

Despite those talks, tension boiled over on May 3, 2023, when radical Meitei-majoritarian mobs—overtly aided by the Meitei dominated state security forces —led widespread attacks on Kuki-Zo settlements in Imphal valley and hamlets bordering the valley and hill districts. Hundreds were killed, many women raped and slaughtered, and thousands displaced – the twin communities or one-time brothers found themselves physically and psychologically severed. Thereafter, stretching over two misery-filled years, the minority Kuki Zo victim have only waited for Government to acknowledge their plight and secure safe political separation from Meitei dominated Manipur with Constitutional safeguards.

ALSO READ: As Divides Deepen, Manipur Seeks Answers to May 3 Tragedy Two Years On

A Return to Historical Norms

In the aftermath of this tragedy, many tribal leaders now openly call for direct central rule under modelled on Article 239A (the same provision used to govern Puducherry) for Kuki-Zo areas, with a parallel arrangement for their Naga neighbours, alongside autonomous Meitei administration in the valley. The Puducherry model would amicably address overlapping land issues in the existing hill districts that were established not on ethnic lines, but for administrative convenience. They argue that only by formally acknowledging the pre-colonial—and pre-1949—status quo can the three communities, Naga, Kuki Zo and Meitei, hope to rebuild mutual trust and be reconciled as good neighbours that would nurture a stable symbiotic relationship.

‘Separate administration isn’t separatism’, insists Mr V Haokip, a Kuki-Zo academic. ‘It’s recognition of historical realities and a proven foundation for peaceful coexistence, and a promise that neither community will be ruled at the whim of the other.’

ALSO READ: SEBI accuses Gautam Adani’s nephew Pranav of Insider Trading

Constitutional experts note that India’s federal framework already accommodates a wide variety of arrangements—states, union territories, Fifth and Sixth Schedule areas—to reflect linguistic, cultural and tribal diversity. Manipur’s mixed model, they say, is an anomaly born of colonial bureaucracy, not organic evolution.

Obstacles and the Road Ahead

Critics of this proposal warn that formal separation risks fragmenting the state beyond repair or setting a precedent for similar demands elsewhere. This argument, made against Kuki Zo political demand, is flawed given the pre-colonial history of separate administration. Legitimacy of the demand is accentuated by the state-sponsored ethnic cleansing commencing 3 May 2023. No other state or Union territory were created under similar circumstances. Proponents also counter that ‘separation’ need not mean secession. Rather, it can be a form of internal autonomy that keeps both administrations firmly within the Union of India. The reasoning is congruent with the visionary Constitutional fathers, who envisaged the needs for a growing nation and enshrined provisions under Article 3 to create new states and Union Territories, not to break or weaken, but to strengthen the Union.

To move forward, they urge: Invoke a transitional central administration modelled on Article 239A in Kuki-Zo regions with a parallel arrangement for the Naga-majority regions.

Conclusion

More than two centuries after their first encounter with British ‘divide-and-rule’, the Meitei and Kuki Zo once again stand at a crossroads. The surge in violence since May 2023 has shattered the illusion that a one-size-fits-all administration can guarantee peace. As Manipur’s leaders and Government of India debate the path ahead with the United People’s Front and the Kuki National Organisation, one thing is clear: any lasting solution must respect the historical—and constitutional—right of each community to govern its own affairs. In the words of historian Dr Thangjam, ‘To build a unified tomorrow, we must first honour the separations of our past.’