Home Minister Amit Shah’s plan to reopen Manipur’s highways by March 8 lies in tatters, with no movement between the Kuki-Zo hills and Meitei valley. Clashes that killed one and injured dozens linger, as distrust and blockades choke daily life.

BY Navin Upadhyay

April 9, 2025 – One month has passed since Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s March 8 deadline to restore free movement of vehicles on Manipur’s highways, yet the state remains trapped in a standstill. The ambitious directive, aimed at bridging the ethnic divide between the Meitei-dominated Imphal Valley and the Kuki-Zo-dominated hills, has failed to yield progress. The shadow of violent protests on March 8—led by Kuki-Zo women—still looms large, with one youth killed and nearly 70 women injured in clashes with security forces. Today, private vehicles remain off the roads, Kukis cannot travel to the valley, and Meiteis steer clear of the hills. The situation, far from improving, underscores the deep-seated mistrust and logistical challenges plaguing Manipur.

A Deadline Marred by Violence

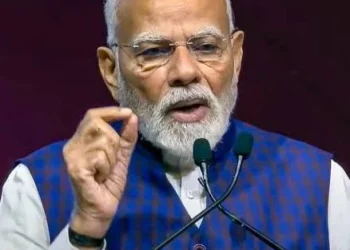

On March 1, Amit Shah chaired a high-level security review in New Delhi, setting March 8 as the date to resume unrestricted movement across Manipur’s highways. The plan included escorted bus services connecting Imphal to Senapati via Kangpokpi and to Churachandpur via Bishnupur—routes cutting through Meitei, Kuki-Zo, and Naga areas. However, the initiative unraveled on its first day. In Kangpokpi, Kuki-Zo protesters, including women, blocked National Highway-2, burning tires and pelting stones at a state transport bus. Security forces responded with tear gas and blank rounds, but the confrontation escalated, leaving 19-year-old Lalgouthang Singsit dead and dozens injured. The Kuki-Zo Council called an indefinite shutdown, and the Committee on Tribal Unity (COTU) vowed to bar Meitei vehicles until their demand for a separate administration is met.

The road that is more important than two years of hell in Manipur?

The alternative route to India’s biggest psychological worry- the chicken neck! Will do anything to get this road operational including even embracing the devil!

Manipur? Do I give a damn for these chinkies… pic.twitter.com/A9vEm9V9L9— नरेशचन्द्र (@nareshchandra_1) April 9, 2025

The violence shattered hopes of reconciliation. A month later, the highways remain choked, with neither community willing to cross the invisible ethnic lines drawn since the conflict erupted in May 2023. Talks between Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) officials and Kuki-Zo and Meitei groups in mid-March yielded no resolution, as both sides clung to entrenched positions.

ALSO READ: Kuki Inpi Slams Biren Singh Over Misleading Claims

Why the Stalemate Persists

The failure to restore free movement stems from a toxic blend of political deadlock, community distrust, and logistical hurdles. The Kuki-Zo community, concentrated in the hills, insists on a separate Union Territory, citing decades of marginalization and the state government’s alleged bias toward the Meiteis. They view Shah’s directive as a forced imposition that ignores their security concerns. “Free movement sounds noble, but it’s a death sentence for us without a political solution,” a tribal youth said, referencing past attacks on Kukis in Meitei areas.

Conversely, Meitei groups like the Federation of Civil Society Organisations (FOCS) accuse Kuki-Zo leaders of sabotaging peace efforts. Their planned “March to the Hills” on March 8—intended as a peace gesture—was halted by security forces amid Kuki objections, further fueling resentment. “They blocked our highways and demand separation, but we won’t let Manipur be divided,” is the refrain among the Meitie civil organisaitons.

Security forces, tasked with enforcing Shah’s order, face an impossible bind. While they’ve dismantled some civilian checkpoints since President’s Rule was imposed on February 13, armed “village volunteers” from both communities continue to monitor roads. Buffer zones, meant to prevent clashes, have instead become no-go areas, with reports of sporadic gunfire and abductions persisting.

Hardships Mount for Both Communities

The impasse has deepened the humanitarian crisis in Manipur, where ethnic violence has already claimed over 250 lives and displaced 60,000 people. For the Kuki-Zo in the hills, the lack of free movement cuts off access to critical services in Imphal. The city’s airport, a lifeline for travel, remains out of reach, forcing reliance on costly helicopter services few can afford. Major hospitals, concentrated in the valley, are inaccessible, leaving the sick and injured dependent on under-equipped local facilities.

Meiteis in the valley face their own struggles. National Highways 2 and 37—linking Imphal to Nagaland and Assam—are vital for essential supplies like fuel, food, and medicine. Blockades by Kuki protesters have driven up prices, with petrol selling at double the usual rate on the black market.

ALSO READ: Tariff Ping Pong: China Hits Back with 84% Tariffs on US Goods Starting Thursday

A Grim Outlook

As Manipur marks one month since Shah’s unmet deadline, the prospect of free movement feels more distant than ever. The state, under President’s Rule since the resignation of Chief Minister N. Biren Singh, teeters on the edge of further unrest. Kuki-Zo groups refuse to relent until their political demands are addressed, while Meitei organizations push for territorial integrity. Security forces, despite recovering over 300 looted weapons, struggle to restore order amid a fractured landscape.

For ordinary citizens, the cost is immediate and personal. Kukis miss flights and medical care; Meiteis grapple with shortages and isolation. The highways, once arteries of connectivity, now symbolize division. Without a breakthrough—political or otherwise—Manipur’s wounds will only deepen, leaving Amit Shah’s vision of mobility a distant dream.

ALSO READ: From Dialogue to Discord: Meitie Groups Differ Over MHA Peace Initiative