An administrative order declaring Litan Bazar as ancestral Tangkhul land has triggered sharp resistance from Kuki bodies, revealing how unresolved land claims can rapidly escalate into ethnic conflict.

By PC Bureau

February 2026: The violence that engulfed Litan Sareikhong village in Ukhrul district on February 7–8, 2026, cannot be reduced to a sudden breakdown of law and order. Beneath the flames, displacement, and fear lies a deeper, unresolved conflict — one shaped by contested land claims, historical memory, parallel systems of authority, and the dangerous politicisation of identity.

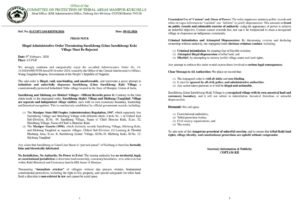

A drunken brawl may have triggered the present clash, but the conflict has since taken a far more dangerous turn with the emergence of an Administrative Order issued on October 8, 2024, by the Central Administrative Officer of the Wung Tangkhul Region under the self-proclaimed Government of the People’s Republic of Nagalim (GPRN).

The directive declared Litan/Litan Bazar as ancestral land of Sikibung/Sharkaphung village, asserting Tangkhul Naga customary ownership and ordering the chief of Sareikhong Kuki village to submit to the decision or face eviction under Naga customary law. The order, invoking “tradition, folklore, and custom,” effectively overrides statutory land records and constitutional protections, injecting a volatile legal and political dimension into what began as a local altercation.

READ: Delhi Police Register Case Over Leak of Gen Naravane’s Memo

This order has now been sharply contested by the Committee on Protection of Tribal Areas Manipur – Kuki Hills (COPTAM-KH), which, in a detailed press note dated February 9, 2026, rejected it as illegal, unconstitutional, and dangerously coercive. The clash between these two positions exposes not merely a local land dispute, but a fundamental collision between customary authority and constitutional governance.

Custom, Court, and Competing Claims

The GPRN order rests on three principal arguments. First, it asserts that Litan/Litan Bazar has historically formed part of Sikibung/Sharkaphung village under Tangkhul Naga tradition and folklore. Second, it refers to a 1973 settlement agreement, under which the Sareikhong chief allegedly agreed to pay ₹20,000 in exchange for peaceful settlement, of which only half was paid. The failure to pay the remaining amount by July 31, 1974, it claims, automatically annulled the agreement under Naga customary law. Third, it maintains that a competent civil court had adjudged Litan to be part of Sikibung’s ancestral land.

On this basis, the order directed the Sareikhong chief to respect Naga tradition and “settle in peace,” warning that any violation would invite immediate eviction.

In a press note issued on Monday, COPTAM-KH described the Administrative Order No. 14-11/2024/ORD/WTR dated October 8, 2024, as “illegal, void, non-binding, and unenforceable.” The organisation accused the issuing authority of attempting to intimidate and unlawfully dispossess the indigenous Kuki community of Sareikhong, a constitutionally protected Scheduled Tribe village in Manipur.

COPTAM-KH asserted that Sareikhong and Sikibung are distinct and independent village entities, each possessing its own customary boundaries, leadership, and historical recognition. This position, it said, is firmly supported by official government records, including the Manipur Village and Hill Peoples (Administration) Regulation, 1947, which separately lists Sareikhong and Sikibung villages with different chiefs, and the Manipur Gazette (1956), which records Sareikhong, Sikibung Kuki, and nearby settlements as distinct villages under Ukhrul Sub-Division.

Rejecting claims that Sareikhong or Litan Bazar is “part and parcel” of Sikibung, the committee termed such assertions “factually false and historically fabricated.” It alleged that the impugned order selectively invokes vague notions of “custom” and “tradition” while suppressing statutory public records, amounting to fraud on public records and a colourable exercise of authority. The directive’s threat of “immediate eviction” without due process, the committee argued, violates fundamental constitutional protections, including the right to life and property, as well as special safeguards accorded to tribal land under the Constitution of India.

COPTAM-KH further contended that the issuing authority—operating under the banner of the “Government of the People’s Republic of Nagalim (GPRN)”—possesses no territorial, legal, or constitutional jurisdiction to adjudicate land ownership, redraw customary boundaries, or order evictions within Kuki historical and customary areas of Manipur’s hill districts.

Houses burned in Litan area of Ukhrul, #Manipur.

Tension between the Kukis and Nagas had been escalating these past few days.

We sure know who started it!! The pseudo victims will be very active with their propaganda all over. https://t.co/fZmcbKJoWx pic.twitter.com/1Nx6qLr5xf

— 𝒃𝒊𝒏𝒊 (@Echoes4mAshes) February 8, 2026

Flagging potential criminal liability, the committee cited criminal intimidation through threats of forcible eviction, attempted illegal dispossession of tribal land, and mischief aimed at undermining lawful village land and identity. It warned that any attempt to enforce the order would invite “serious legal consequences”, and called upon all civil, police, and administrative authorities to ignore the directive as void ab initio.

In its appeal, COPTAM-KH urged constitutional authorities, tribal protection bodies, civil society organisations, and the media to take cognisance of what it termed a “dangerous precedent of unlawful coercion,” and to ensure that tribal Kuki land rights, village identity, and constitutional safeguards are upheld without compromise.

COPTAM-KH’s rebuttal directly challenges both the legality and legitimacy of these claims. The committee argues that vague references to tradition and folklore cannot override statutory land records, and that invoking “custom” to justify dispossession amounts to fraud on public records and abuse of authority.

More fundamentally, it states that the issuing authority lacks any territorial, constitutional, or statutory jurisdiction to adjudicate land ownership or order eviction within the Hill Areas of Manipur, which fall under India’s constitutional framework and special protections for tribal land.