Ladakh Protesters questioned why their lands remain vulnerable when tribals in Assam, Mizoram, and Tripura enjoy constitutional safeguards.

By Navin Upadhyay

September 27, 2025

Ladakh’s tribal communities are intensifying their demand for Sixth Schedule protection, asking the Modi Government a blunt question: “If you don’t want to grab our land, why not give us Sixth Schedule?” This growing frustration reflects a deep distrust after six years of unfulfilled promises. Tribal leaders warn that without constitutional safeguards, their land, culture, and livelihoods remain exposed to corporate exploitation, particularly for large-scale renewable energy projects.

When Ladakh was carved out of Jammu and Kashmir in 2019 and made a Union Territory, the BJP assured local tribal bodies that special protections akin to the Sixth Schedule would be extended. However, six years later, no legal framework has been instituted. For Ladakhis—over 95% of whom are Scheduled Tribes—the delay raises serious concerns that the Centre may be keeping the region vulnerable for corporate entry.

“A common refrain among protesters has been: why the hesitation in granting us Sixth Schedule safeguards, when the same protections already exist for tribals in Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura?

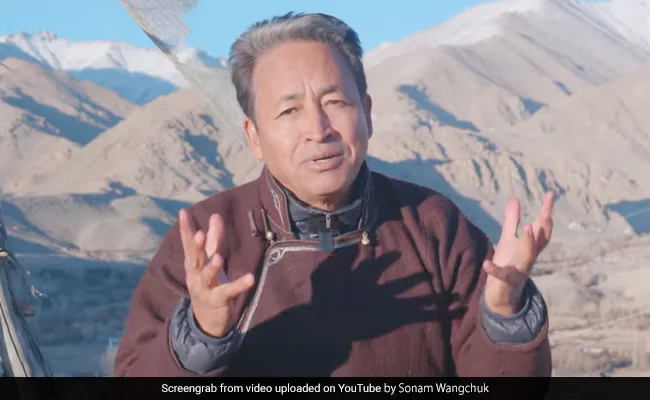

READ: Sonam Wangchuk’s Legacy Stands Tall Amid NSA Charges

Corporate Interests and Land Grab Fears

Social media reports of corporate giants exploring large tracts of land for solar projects have only intensified these fears. Tribal leaders argue that without constitutional protection, these lands could be handed over to private enterprises, echoing patterns seen elsewhere in India.

Sonam Wangchuk, the Ladakhi environmentalist and activist, has repeatedly warned: “Without Sixth Schedule protection, Ladakh is wide open for plunder. Development without safeguards will turn this land into a corporate colony. Our people, our heritage, and our future generations will pay the price.”

The concern is grounded in experience. In Fifth Schedule areas like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha, tribal lands have been repeatedly handed over to mining and industrial companies despite legal protections. Civil society activists note that even when safeguards exist, enforcement is weak, leaving communities at the mercy of political and corporate interests.

READ: Analysis: NIA Terror Case Lacked Even Prima Facie Evidence — Was Mate Framed?

Distrust Beyond Ladakh

The fear is not limited to solar projects. Tribal communities point to a national pattern of land dispossession, citing Assam, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and the Nicobar Islands as examples where ancestral lands have been handed to corporations. A youth activist in Kargil remarked, “If governments are willing to dilute protections elsewhere, why should we believe Ladakh will be any different?”

Water systems fed by glaciers, high-altitude pastures critical for livestock, and centuries-old cultural practices are all at stake. Without Sixth Schedule protections, the land may become legally vulnerable, opening the door to commercial exploitation that could irreversibly alter Ladakh’s fragile ecology.

Is India becoming a banana republic?

—Sonam Wangchuk 4 weeks ago pic.twitter.com/AuaIpsrXVD

— Mohit Chauhan (@mohitlaws) September 26, 2025

Political and Social Fallout

The BJP’s inaction is already having political consequences. Independent candidates and regional parties championing tribal rights are gaining ground in local elections.

Civil society groups are intensifying their agitation. In the aftermath of the recent violence in Leh, the Kargil Democratic Alliance accused the Union Government of betraying the people of Ladakh by ignoring their longstanding demands. A KDA leader stated,

“For the last five years, Ladakh has been protesting in favour of a four-point program: statehood, inclusion under the Sixth Schedule, job security, and reservation safeguards. In 2019, our political and democratic rights were snatched away, and our land and jobs were left vulnerable.

The concerns are echoed widely across Ladakh. A post on social media, said: “The government talks of making Ladakh the ‘solar capital of India.’ But what about our rights? Without safeguards, we will be reduced to laborers on our own land.”

Students, women’s groups, and farmers all echo this sentiment. They insist that the Sixth Schedule is not about blocking development—it is about ensuring development is just, sustainable, and under local control.

For Ladakh’s tribal population, this struggle is existential. Constitutional protections could safeguard the region’s ecology, livelihoods, and culture, ensuring that development does not come at the cost of dispossession.

The standoff now leaves the BJP with a crucial choice: either reassure Ladakh’s tribals through legal protection or risk being perceived as complicit in opening their lands to corporate exploitation. For many Ladakhis, the Sixth Schedule is more than policy—it is the difference between survival and dispossession, autonomy and alienation.