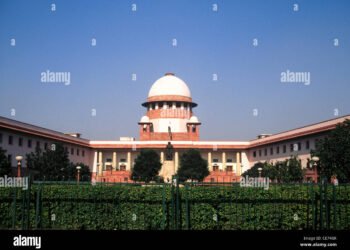

In a groundbreaking 4:3 decision, the Supreme Court overturned a 1967 judgment preventing Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) from claiming minority status. The court has now tasked a three-judge bench with resolving AMU’s minority status, reigniting a long-standing debate on the university’s identity and autonomy.

By PC bureau

In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court, by a narrow 4:3 majority, overturned its 1967 judgment that previously barred Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) from claiming minority status. The ruling left the final determination on AMU’s status to a separate three-judge bench, which will address the question directly.

The 1967 decision in Azeez Basha vs Union of India had established that institutions created by statute could not be considered minority institutions. Chief Justice DY Chandrachud, delivering his final verdict before retirement, was joined by Justices Sanjiv Khanna, JB Pardiwala, and Manoj Misra in forming the majority opinion. Justices Surya Kant, Dipankar Datta, and SC Sharma dissented.

This decision follows a plea challenging the 2006 Allahabad High Court ruling, which similarly held that AMU does not qualify as a minority institution. The Supreme Court’s order opens a new chapter in the ongoing legal debate over AMU’s minority status, with further deliberation now set to proceed.

The central issue before the bench was: What are the criteria for treating an educational institution as a minority educational institution? Specifically, the question was whether an institution would be regarded as a minority institution based on the fact that it was established by individuals belonging to a religious or linguistic minority, or whether it is sufficient for the institution to be administered by such individuals.

The bench considered four main aspects:

- Whether a university, established and governed by statute (the AMU Act of 1920), can claim minority status.

- The correctness of the 1967 Supreme Court judgment in S. Azeez Basha vs. Union of India (a 5-judge bench) that denied minority status to AMU.

- The legal nature and correctness of the 1981 amendment to the AMU Act, which granted minority status to the university post-Basha.

- Whether the Allahabad High Court’s reliance on the Basha judgment in AMU v. Malay Shukla (2006) to conclude that AMU, as a non-minority institution, could not reserve 50% seats for Muslim candidates in Medical PG courses was justified.

A detailed explainer on the issue of AMU’s plea for minority status and the arguments raised by the parties is available on Live Law.

Key Highlights from the Judgment

Majority View

- The Court held that Article 30 would be diluted if it were applied prospectively only to institutions established post-constitutional commencement.

- The terms “incorporation” and “establishment” should not be conflated. Just because AMU was incorporated by an imperial statute does not negate that it was established by a minority. The Court emphasized that a formalistic reading of the statute would defeat the objectives of Article 30.

- To determine the establishment of the institution, the Court would need to trace its origins and identify the “brain” behind its establishment, emphasizing whether members of the minority community played a significant role in the founding and funding of the institution.

- The Court clarified that it is not necessary for an institution to be established solely for the benefit of the minority community or for the minority to control its administration. Minority educational institutions can emphasize secular education without the need for minority members in the administration.

- The Court overruled the 1967 Azeez Basha judgment and directed that the minority status of AMU be decided based on the new criteria set forth in this case. It further directed that the papers be placed before the Chief Justice to constitute a bench to decide the issue and the correctness of the 2006 Allahabad High Court judgment.

Justice Surya Kant’s View

Justice Surya Kant took exception to the reference order passed in the Anjuman case in 1981, which directly referred the matter to a 7-judge bench. However, he upheld the 2019 reference made by a bench led by the then Chief Justice as maintainable.

- A minority can establish an institution under Article 30, but it must be recognized by a statute and by the University Grants Commission (UGC). He opined that the Azeez Basha judgment needed modification.

- Justice Surya Kant held that there is no conflict between Azeez Basha and the 11-judge bench decision in TMA Pai Foundation vs. State of Karnataka.

- Institutions under Article 30(1) include universities, and for a minority institution to receive protection under Article 30, it must satisfy both criteria of being established and administered by a minority.

- The legislative intent behind the statute incorporating a university or institution is crucial in determining its minority status.

- The question of whether AMU is a minority institution remains a mixed question of law and fact, to be decided by a regular bench.

Justice Dipankar Datta’s View

Justice Datta made a categorical declaration that AMU is not a minority institution, holding that the references in both 1981 and 2019 were unnecessary.

Justice SC Sharma’s View

Justice Sharma opined that the minority community must control the administration of the institution without any external influence. He emphasized that educational institutions under Article 30 must offer secular education and that the minority should have full administrative control.

- He further argued that the terms “established” and “administered” must be applied conjunctively, meaning that the minority must have a decisive role in both the creation and functioning of the institution.

- The control over hiring and firing of staff should lie with the minority, and overall authority should rest with them.

- Justice Sharma emphasized that Article 30 is meant to ensure equal treatment for all, and there is no need for a separate educational setup for minorities, as they are now well-integrated into mainstream opportunities.

Case Reference Trajectory

The formation of a 7-judge bench follows a 2019 reference order issued by a 3-judge bench led by then CJI Ranjan Gogoi. This reference arose from an appeal against the 2006 Allahabad High Court judgment.

Prior to this, the issue had been referred multiple times:

- In 1967, the Supreme Court ruled in S. Azeez Basha vs. Union of India, rejecting AMU’s claim to minority status.

- In 1981, a reference in Anjuman-e-Rahmania Vs. District Inspector of Schools forwarded the question of minority status to a 7-judge bench, which, along with other cases, eventually led to the formation of the current bench.

- An 11-judge bench, which dealt with the TMA Pai case, refrained from addressing the minority status issue, leaving it to a regular bench to decide.

The senior counsels representing AMU included Dr. Rajeev Dhavan, Mr. Kapil Sibal, and others. The Union of India was represented by Attorney General R Venkataramani, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, and several other senior counsels.

(This summary of the key deliberations and judgment regarding AMU’s plea for minority status is sourced from Live Law.)